Here are parts eight and nine of my thirteen part commentary and synopsis of the master piece by Bessel van der Kolk. Much of this post is a verbatim reprint from The Body Keeps The Score. One in ten people have alexithymia, problems feeling and expressing emotions. The Greek word alexithymia means “no words for emotions.”

1. INTRODUCTION: Childhood Trauma Causes Addiction

2. 12 Steps & 12 Traditions: Damaging Emotional Conflicts

3. Trauma Damages Left Brain Speech

4. BIOFEEDBACK: Meditative States of Consciousness

5. INTEROCEPTION: Traumatic Awareness

6. What Were You Thinking Right Before You Acted Out Your Childhood Trauma?

7. Communication is the Opposite of Trauma

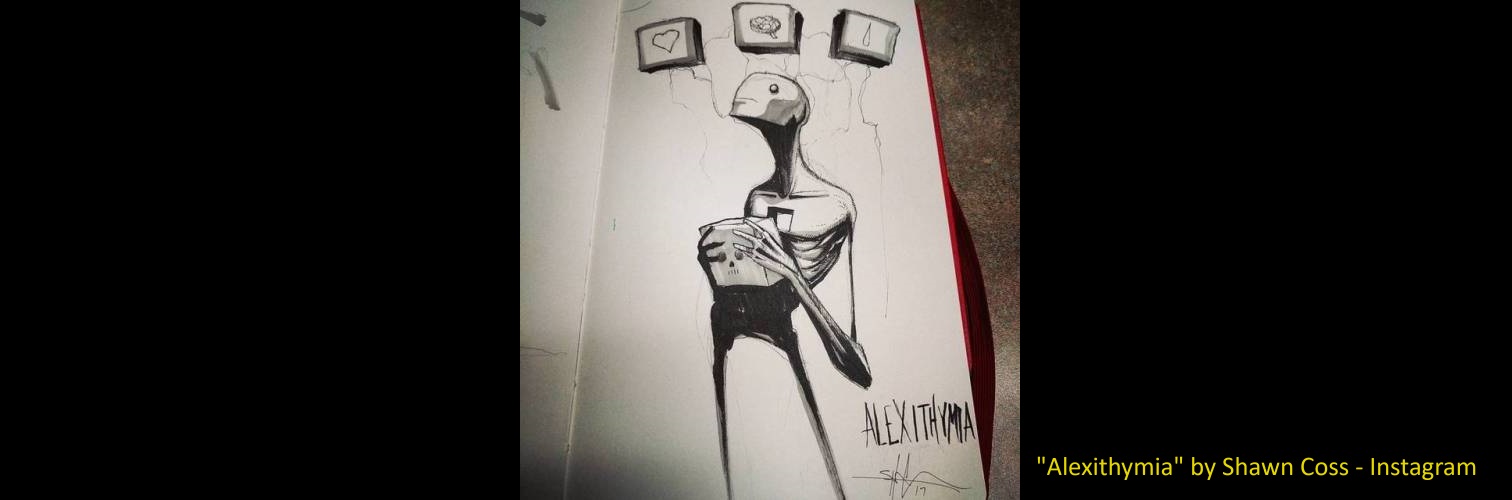

8. ALEXITHYMIA: Inability to Feel Emotion

9. EMDR Reprocesses Body Awareness and Does Not Visit the Original Trauma in Detail

10. EMDR is for Patients So Traumatized That Full Recovery is Thought to Be Impossible.

11. Lock Down Your Childhood Trauma Instead of Acting it Out

12. Final Healing: The Patient’s Internal Landscape Manifests Critical Mass of Self

13. Eye Movement Desensitizing Reprocessing of Traumatic Memories

8. ALEXITHYMIA: Inability to Feel and Express Emotion

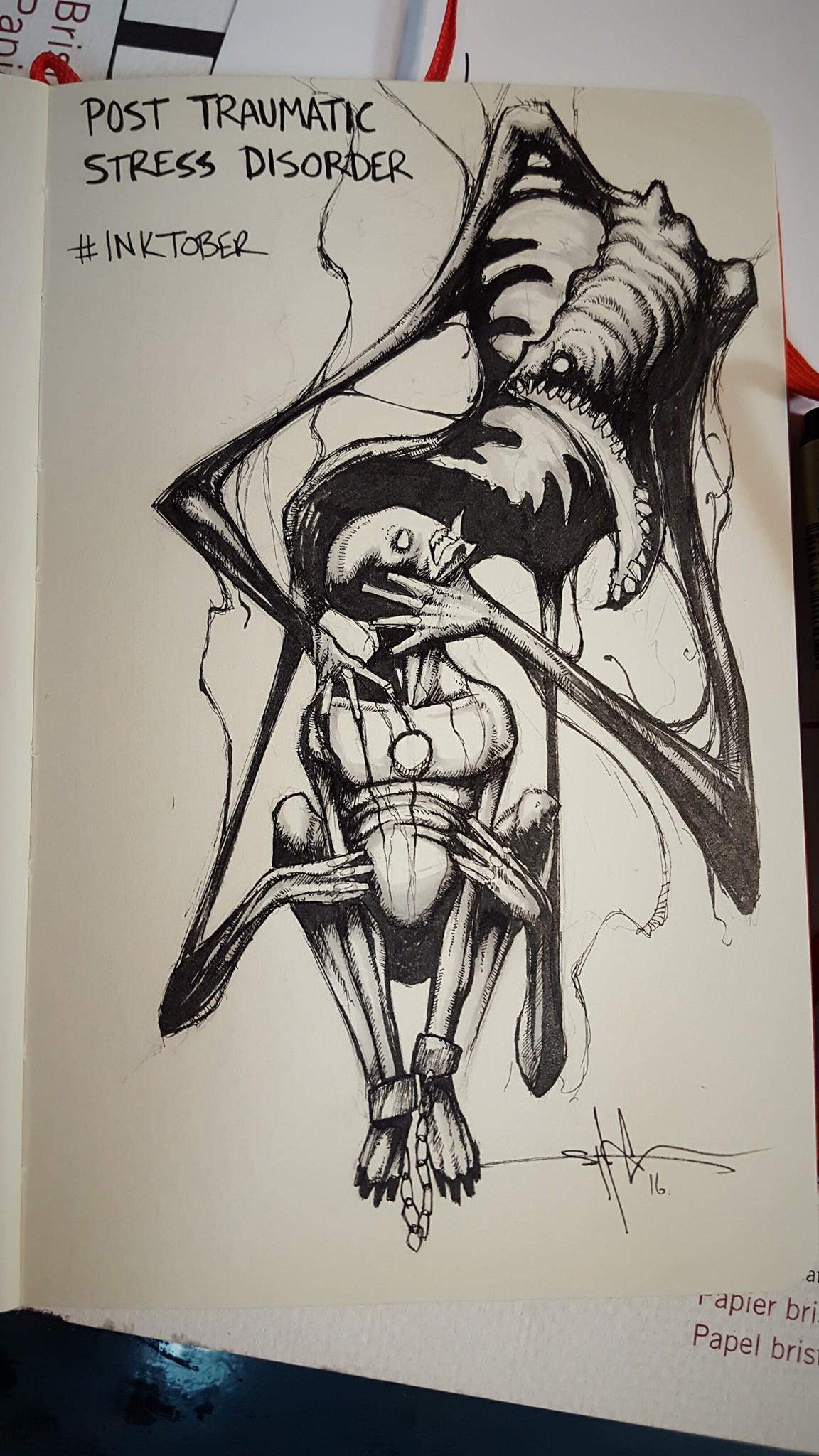

“The reason that traumatized people become overwhelmed by telling their stories, and the reason they have cognitive flashbacks, is that their brains have changed. As Freud and Breuer observed, trauma does not simply act as a releasing agent for symptoms. Rather, ‘the psychical trauma-or more precisely the memory of trauma acts like a foreign body which long after its entry must continue to be regarded as an agent that is still at work.‘ Like a deep seated splinter that causes an infection, it is the body’s response to the foreign object that becomes the problem more than the object itself.” –The Body Keeps the Score

Brain Damage

“Modern neuroscience solidly supports Freud’s notion that many of our conscious thoughts are complex rationalizations for the flood of instincts, reflexes, motives, and deep-seated memories that emanate from the unconscious. Trauma interferes with the proper functioning of brain areas that manage and interpret experience. A robust sense of self–one that allows a person to state confidently, “This is what I think and feel” and “This is what is going on with me”–depends on a healthy and dynamic interplay among these areas.” –The Body Keeps the Score

Abnormal Insula

Almost every brain-imaging study of trauma patients finds abnormal activation of the insula. This part of the brain integrates and interprets the input from the internal organs–including our muscles, joints, and balance (proprioceptive) system–to generate the sense of being embodied. The insula can transmit signals to the amygdala that trigger the fight/flight responses. This does not require any cognitive input or any conscious recognition that something has gone awry–you just feel on edge and unable to focus or, at worst, have a sense of imminent doom. These powerful feelings are generated deep inside the brain and cannot be eliminated by reason or understanding. –The Body Keeps the Score

Alexithymia is evidenced by dissociation

“Being constantly assaulted by, but consciously cut off from, the origin of bodily sensations produces alexithymia: not being able to sense and communicate what is going on with you. Only by getting in touch with your body, by connecting viscerally with your self, can you regain a sense of who you are, your priorities and values. Alexithymia, dissociation, and shutdown all involve the brain structures that enable us to focus, know what we feel, and take action to protect ourselves. When these structures are subjected to inescapable shock, the result may be confusion and agitation, or it may be emotional detachment, often accompanied by out-of-body experiences–the feeling you’re watching yourself from far away. In other words trauma makes people feel like either some body else or no body. In order to overcome trauma, you need help to get back in touch with your body, with your Self.” –The Body Keeps the Score

Becoming Some Body

“There is no question that language is essential: Our sense of Self depends on being able to organize our memories into a coherent whole. This requires well-functioning connections between the conscious brain and the self system of the body–connections that are often damaged by trauma. The full story can be told only after those structures are repaired and after the groundwork has been laid: after no body becomes some body.“ —THE BODY KEEPS THE SCORE, pp 248, 249.

9. EYE MOVEMENT DESENSITIZING REPROCESSING (EMDR) DOES NOT REVISIT THE ORIGINAL TRAUMA IN DETAIL

“The factual details of the childhood trauma do not matter as much as the body memory of the images behind the eye movements that are desensitized and reprocessed.” –The Body Keeps the Score

Association and Integration

“Unlike conventional exposure treatment, EMDR spends very little time revisiting the original trauma. The trauma itself is certainly the starting point. But the focus is on stimulating and opening up the associative process. As Prozac/EMDR studies have shown, drugs can blunt the images and sensations of terror. But they remain embedded in the mind and body. In contrast with the subjects who improved on Prozac–whose memories were merely blunted, not integrated as an event that happened in the past, and still caused considerable anxiety–those who received EMDR no longer experienced the distinct imprints of he trauma. It had become a story of a terrible event that had happened a long time ago. As one of Bessel van der Kolk’s patients said, making a dismissive hand gesture: “It’s over.” –The Body Keeps the Score

We don’t know exactly how EMDR works

“While we don’t yet know precisely how EMDR works, the same is true of Prozac. Prozac has an effect on serotonin, but whether its levels go up or down, and in which brain cells, and why that makes people feel less afraid, is still unclear. We likewise don’t know precisely why talking to a trusted friend gives such profound relief, and it is surprising how few people seem eager to explore the question.

EMDR may take a while to become mainstream

Clinicians have only one obligation: to do whatever they can to help their patients get better. Because of this, clinical practice has always been a hotbed for experimentation. Some experiments fail, some succeed, and some, like EMDR, dialectical behavior therapy, and internal family systems therapy, go on to change the way therapy is practiced. Validating all these treatments takes decades and is hampered by the fact that research support generally goes to methods that have already been proven to work. I am much comforted by considering the history of penicillin: Almost four decades passed between the discovery of its antibiotic properties by Alexander Fleming in 1928 and the final elucidation of its mechanisms in 1965.”—The Body Keeps the Score, pages 263 and 264